What is a Set?

A set is a well defined collection of objects.

Representation of a set.

-

Roster or Tabular Form

-

Set builder or rule method.

-

Roster or tabular form.

For example : v = {a, b, c, d} where v is the set of all alphabets.

-

Set builder or rule method.

Let B = { x : x is an even integer, x > 0} (read as x such x is an even integer, x greater than 0)

orThe set X = {x : x is a real number, 1 < x < 8}, is the set of real numbers that strictly lie between 1 and 8.

-

Universal Set and Empty Set

” If there are some sets under consideration, then there happens to be a fixed set which contains all these given sets. Such a given set is called the Universal Set and is denoted by U.”

For example: In human population studies, the universal set contains all the people in the world.

Empty Set : A set which is empty, denoted by

(read as phi.)

For example : { x : x belongs to N, 2<x<3 } =

Subsets.

If A & B are two sets such that every element in set A is also an element of set B, we can say that A is contained in B or that B contains A.

This can be expressed as :

Let A = {1, 3}, B = {1, 2, 3}, C = {1, 3, 2}

It is also possible while

,

Then, A is a proper subset of B

Properties of Subsets :

- Every set is a subset of itself.

- The empty set is a subset of every set.

- The total number of possible subsets in a given set of symbols is :

Power Set.

Consider the set The subsets of A are :

This family of all the subsets of A is called the Power Set of A, which is denoted by P(A).

Thus,

Cardinality of a Set.

The number of distinct elements obtained in a finite set is called the cardinality or cardinal number of the set.

Example :

Cardinality of an empty set

is 0.

and for a set A, is 5.

The Power Set Theorem.

The Power Set Theorem is a fundamental result in set theory. It states that for any set A, the power set of A (denoted as P(A)) has a strictly greater cardinality than the set A itself. The power set P(A) is the set of all subsets of A, including the empty set and A itself.

Formally, the theorem can be stated as follows:

- Let A be any set. Then, there is no surjective (onto) function from A to P(A).

In other words, ==the power set P(A) of any set A has a cardinality that is greater than the cardinality of A== . This theorem implies that there is no way to pair every element of A with a unique subset of A in such a way that every subset is paired with some element.

Ordered Pairs

An ordered pair of objects is a pair of objects arranged in the same order.

The objects need not be distinct.

For example :

is a well-defined ordered pair.

Cartesian Product of sets.

If A & B are two non-empty sets, the Cartesian Product (or cross product/ direct product) will be :

If or we define

Note:

If A and B are finite sets then :

If either A or B are infinite sets then :

is an infinite set.

For ordered pairs.

A x B is the set of all ordered pairs of the form (a, b) where :

and

Then :

and ,

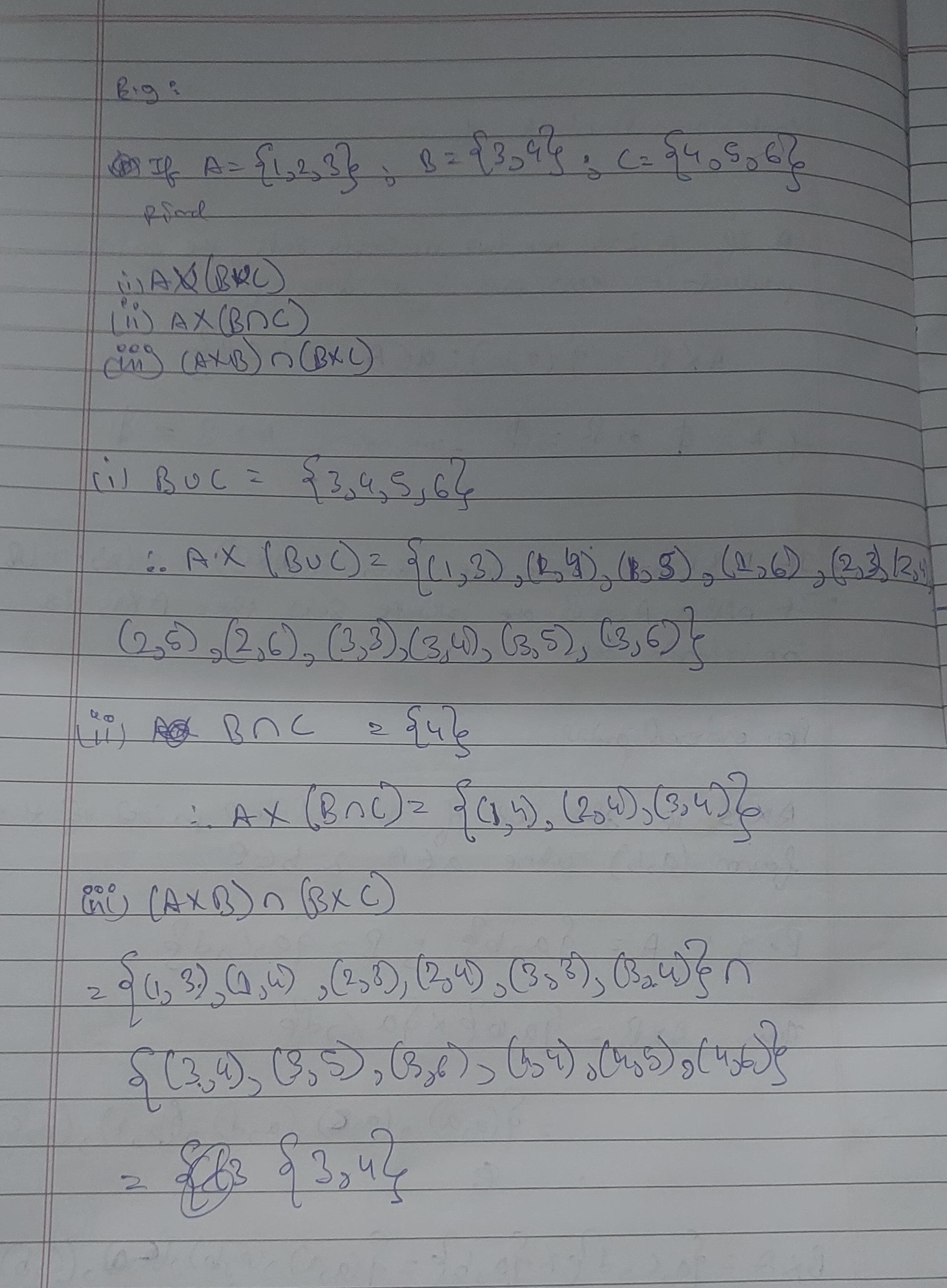

An example on Cartesian Products :

Properties of Cartesian products

For any 3 sets A, B and C (From distributive property.)

-

-

-

For any 4 sets A, B, C and D:

-

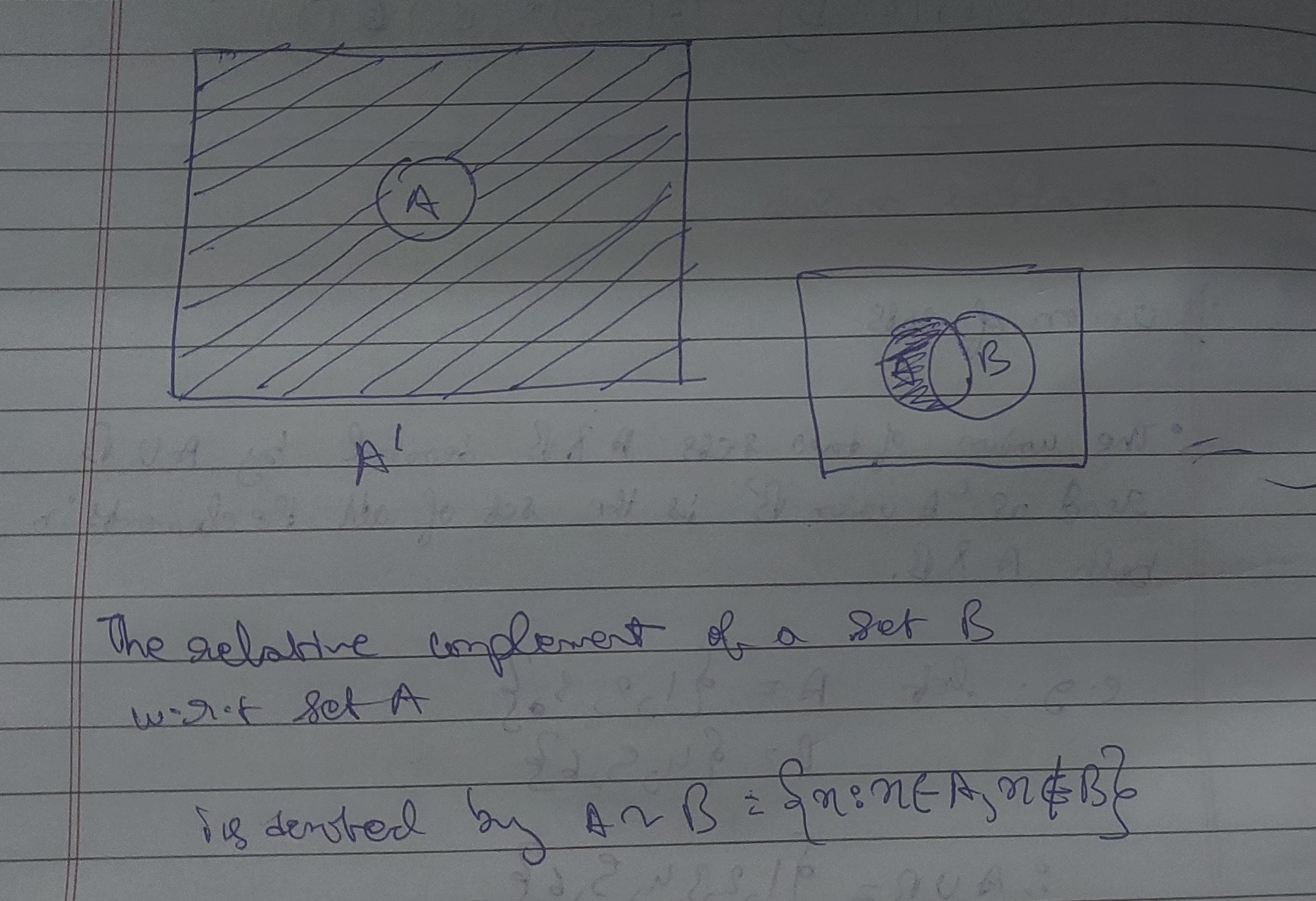

Complement of a set.

Let U be the universal set and let

Then the complement of A, denoted by A’, is the set of elements that belong to U but not to A.

Relative Complement

The relative complement of A w.r.t to B is basically, only the elements in A and nothing from B.

Operations on Sets.

- Union of sets

- Intersection of sets

- Symmetric Difference

1. Union

The Union of two sets A & B denoted by read as ” A union B” is the set of all elements in both A & B.

e.g A = {1, 2, 3}, B = {4, 5, 6}

Therefore,

2. Intersection

The intersection of two sets A & B denoted by :

e.g let A = {1,2,3}, B = {3,4,5}

Therefore,

3. Symmetric Difference

The symmetric difference of sets A & B denoted by

is the set of elements which belong to either A or B but not both.

For example :

or

Here the ”~” operator signifies the relative complement.

For example :

A = {-2, 0 , 1, 2} ; B = {1, 2, 3, 4}

(The elements only in A, not B)

and

(The elements only in B, not A)

Thus,

Countable and Uncountable Sets

Countable Sets

A set is countable if its elements can be put into one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers

This means there exists a bijection (a one-to-one and onto function) between the set and N. Countable sets can be either finite or infinite.

-

Finite sets are trivially countable since they have a limited number of elements. For example, {a,b,c}{a, b, c}{a,b,c} is countable.

-

Infinite countable sets include:

- The set of natural numbers N.

- The set of integers Z.

- The set of rational numbers Q.

Uncountable Sets

A set is uncountable if it cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers. This means there is no bijection between the set and N. Uncountable sets are always infinite and have a greater cardinality than countable sets.

Examples of Uncountable Sets

-

The Real Numbers R: The set of real numbers between any two distinct real numbers is uncountable. The classic proof by Cantor’s diagonal argument shows that the real numbers cannot be listed in a sequence that covers all real numbers.

-

The Interval [0,1]: Even just the real numbers between 0 and 1 form an uncountable set. Cantor’s diagonal argument applies here as well, showing that no matter how you list real numbers in [0,1], some real numbers in this interval will always be left out.

** More on bijective correspondence, Cantor’s diagonal argument below in later sections.

Algebra of Sets

1. Identity Laws :

,

2. Domination Laws :

,

3. Complement Laws :

,

4. Involution Law :

5. Commutative Law:

and

6. Distributive Law:

and

7. De Morgan's Laws :

and

8. Absorption Laws:

and

Relations

In mathematics, expressions such as “is less than”, “is greater than”, “is parallel to”, “is perpendicular”, etc… can be called relations.

Type of Relations :

- Binary Relation

- Reflexive Relation

- Symmetric Relation

- Anti-Symmetric Relation

- Transitive Relation

- Equivalence Relation

Binary Relation

Let A and B be two non-empty sets. Then any subset of R of the cartesian product A x B is called a binary relation R from A to B.

If

we can say “a” is related to “b” and is written as :

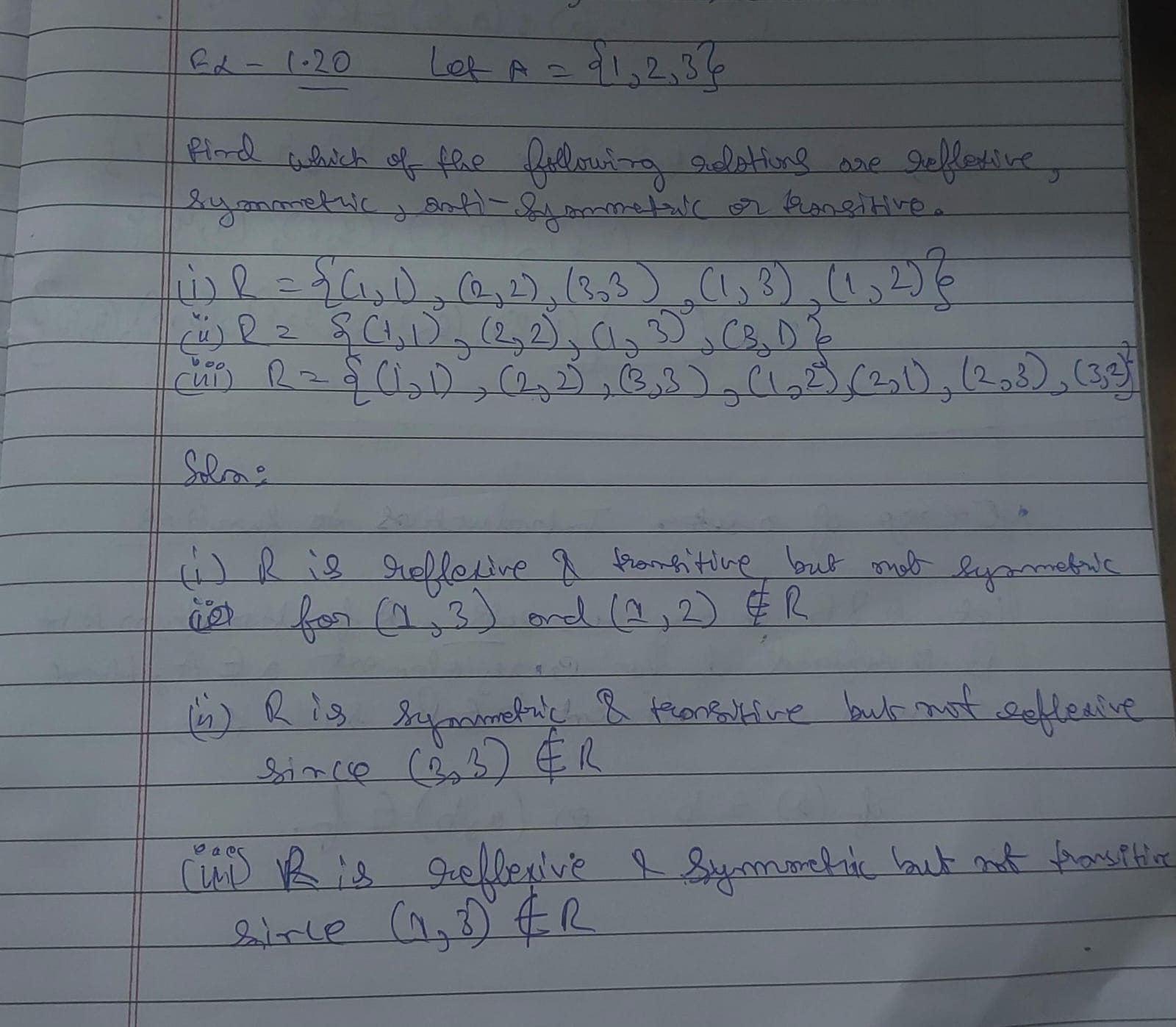

Reflexive Relation

Let R be a relation defined on a set A.

Then R is reflexive, if

For example :

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

then

, R is reflexive.

Symmetric Relation

A relation R defined on a set A is said to be symmetric, if bRa holds whenever aRb holds for

R is symmetric on A if

In simple terms, for any two elements,

,

if their mirror reflection,

then R is symmetric.

Example : A = {1,2,3} ; R = { (2,2), (2,3), (3,2)}

Here for elements (2,3), their mirror reflection (3,2) is present in R as well

Thus, R is symmetric.

Anti-Symmetric Relation

Well, considering the definition of Symmetric relation, a relation is anti-symmetric if for any two elements, their mirror reflection is not present in the relation.

Formal definition:

A relation R on a set A is said to be anti-symmetric if

, if and

then :

Transitive Relation

A relation R on a set A is said to be transitive if any two elements:

,

then ,

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}; R = { (1,1), (2,2), (2,3), (3,2), (3,3)}

Here R is transitive since 2R2, 2R3, belongs to R, also 2R3, 3R2 belongs to R.

Example :

Equivalence Relation

A relation R on a set A is said to be an equivalence relation if R is reflexive, symmetric and transitive at the same time.

Inverse of a relation

Let R be a relation from A to B. Then the inverse of R, denoted by is the relation from R to A, defined by:

Basically the positions of all the elements in R is inverted in the inverse relation.

Example :

A = {2,3,4}, B = {3, 4, 5, 6, 7}, R = { (2,4), (2,6), (3,3), (3,6), (4,4)}

Thus

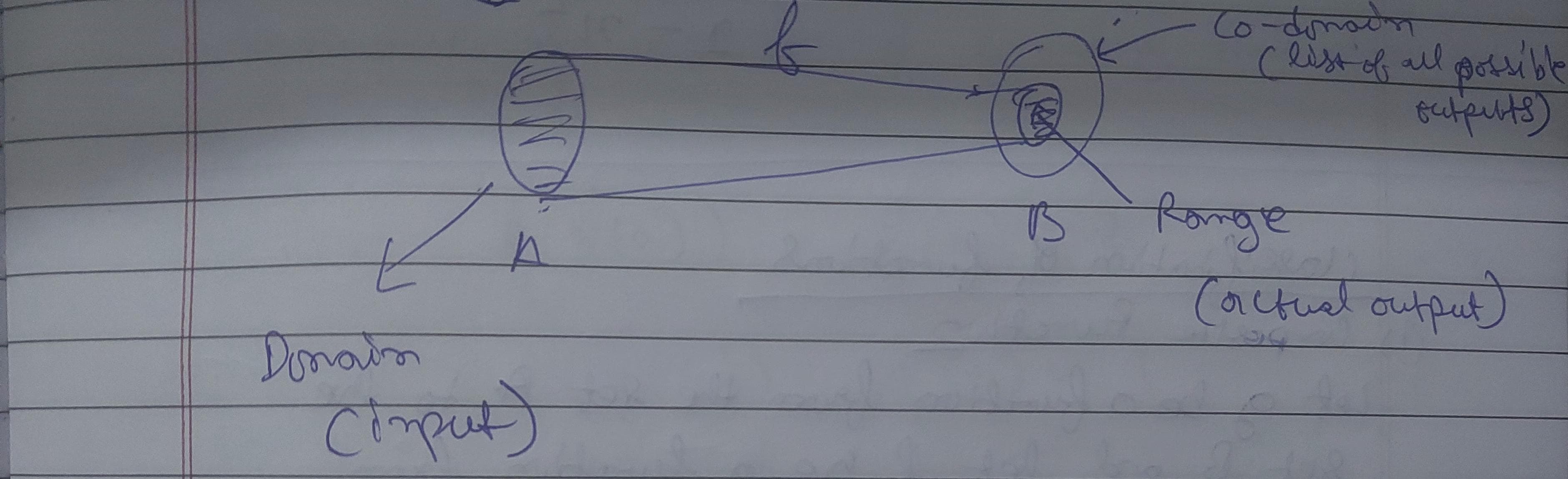

Functions

Let A and B be any two sets. A function from A to B is defined if for every element,

there exists a unique element,

such that

or

Functions are also called mappings or transformations.

A function has the following properties:

- Domain

- Co-domain

- Range

Domain of a function

The domain of a function is basically =the set of inputs= for the function

Co-domain of a function

The co-domain is the set of all possible outputs of the function

Range of a function

The range of a function is the set of all actual outputs of the function

For example

The function F(x) = 2x + 5

Here the set of values of x will the be the domain of F.

Assuming the domain belongs the set of natural numbers N ( > 0)

And here all the possible outputs of the function F, will be the same as the actual outputs as all the values will lie in N.

Or the range will the subset of the co-domain.

for x = 2, F(x) = 9

This belongs in the range.

As well as co-domain since the values go endlessly as they lie in N.

Thus in this case

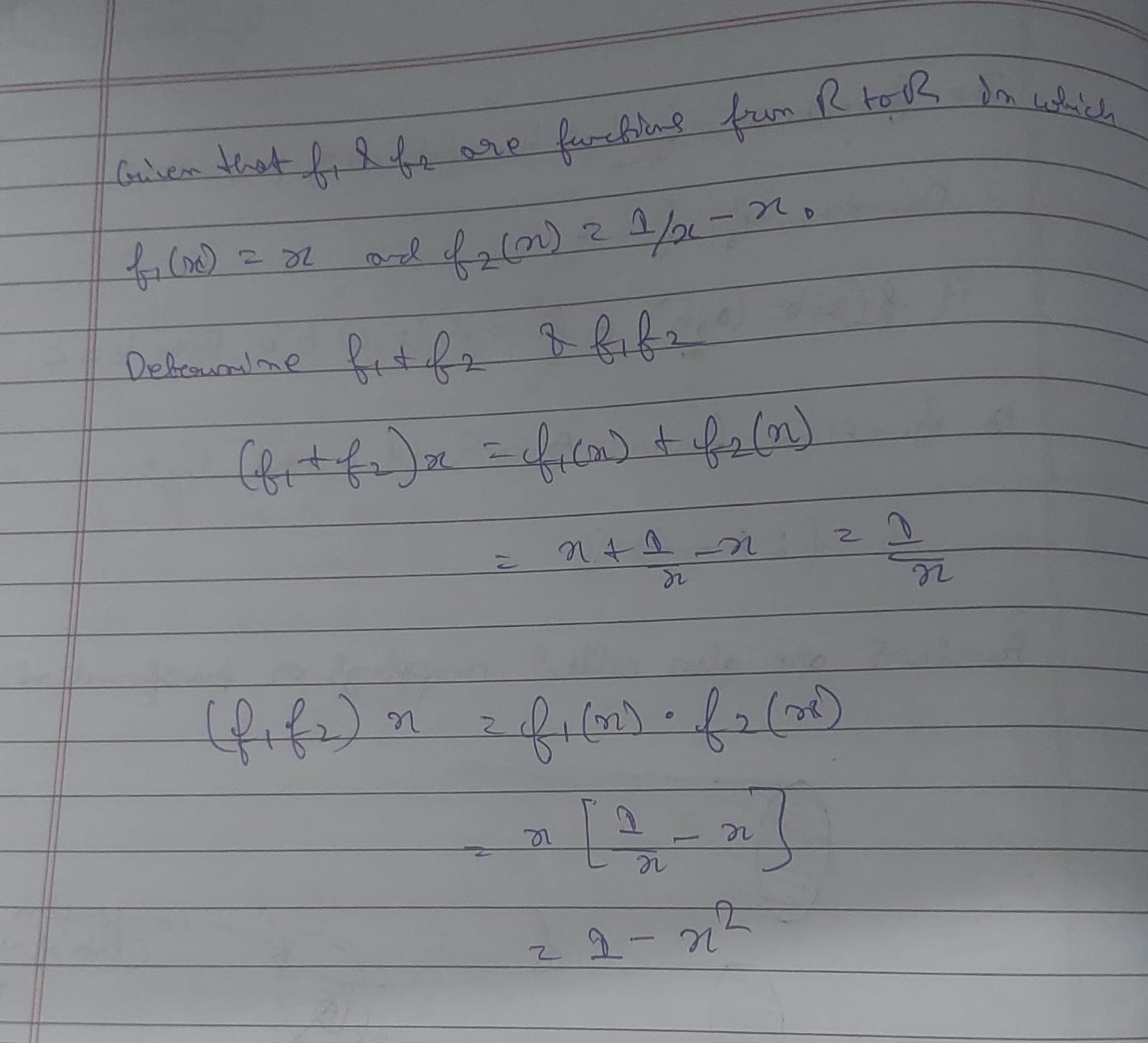

Addition and multiplication of functions

Two real valued functions with the same domain can be added or multiplied or both :

Addition

Multiplication

Classification of Functions

- Injective Function

- Surjective Function

- Bijective Function

- Composite Function

- Inverse function

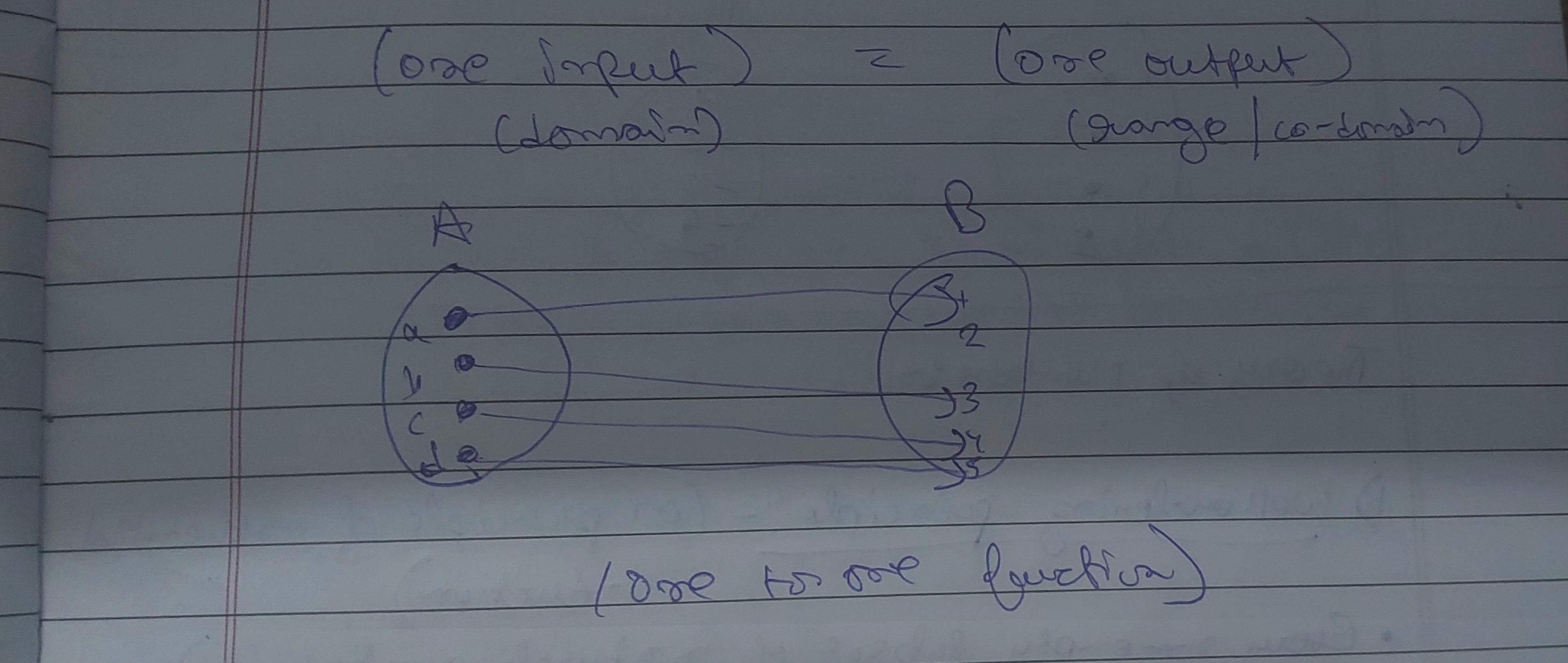

1. Injective Function

An injective (one-to-one) function is a function in which each element in the domain has only one output in the co-domain/range.

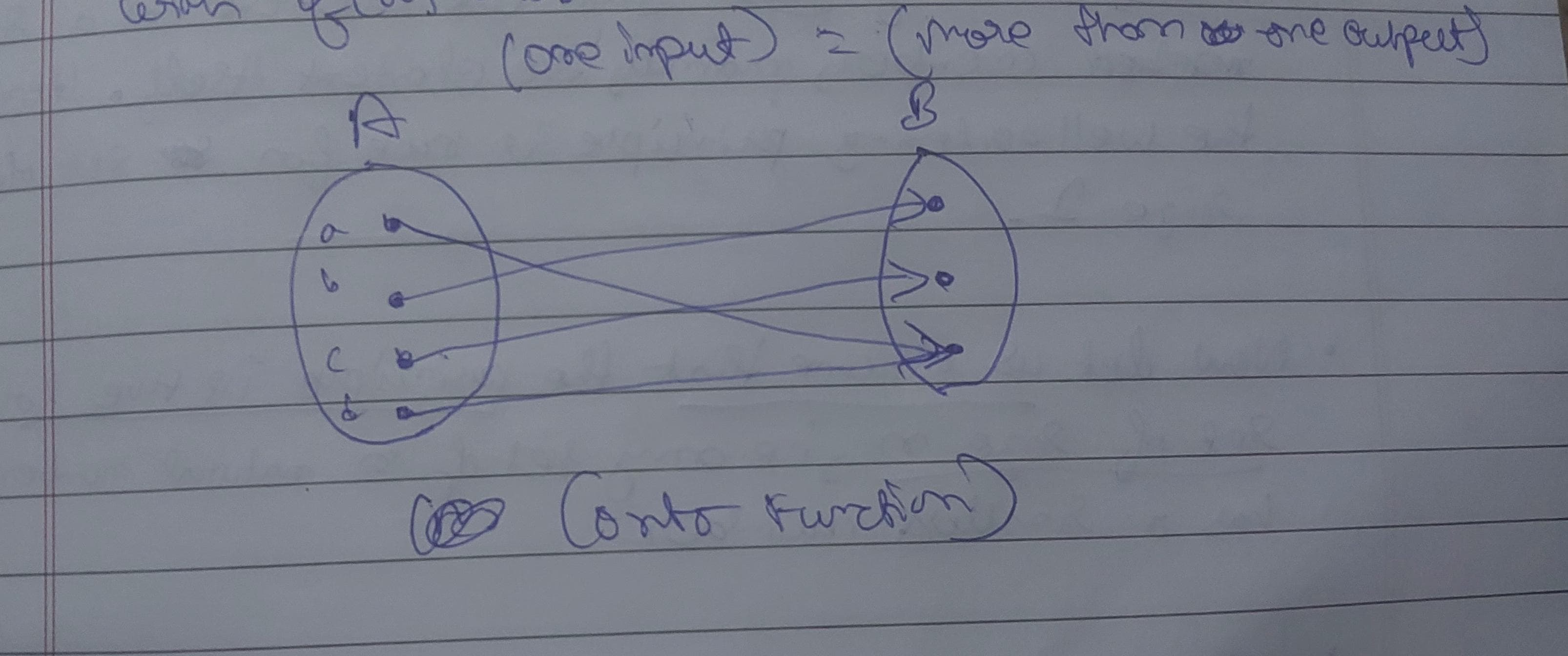

2. Surjective Function

A Surjective (onto) function is a function in which each element has a pre-determined output in the co-domain/range

Small correction in the image, it will be one input = one output.

A function won’t be onto if it is of the following type :

Consider the function :

defined by :

This function is not onto because the element d in the codomain {a,b,c,d} is not mapped by any element of the domain.

3. Bijective Function

A function is bijective when it is both one-to-one and onto at the same time.

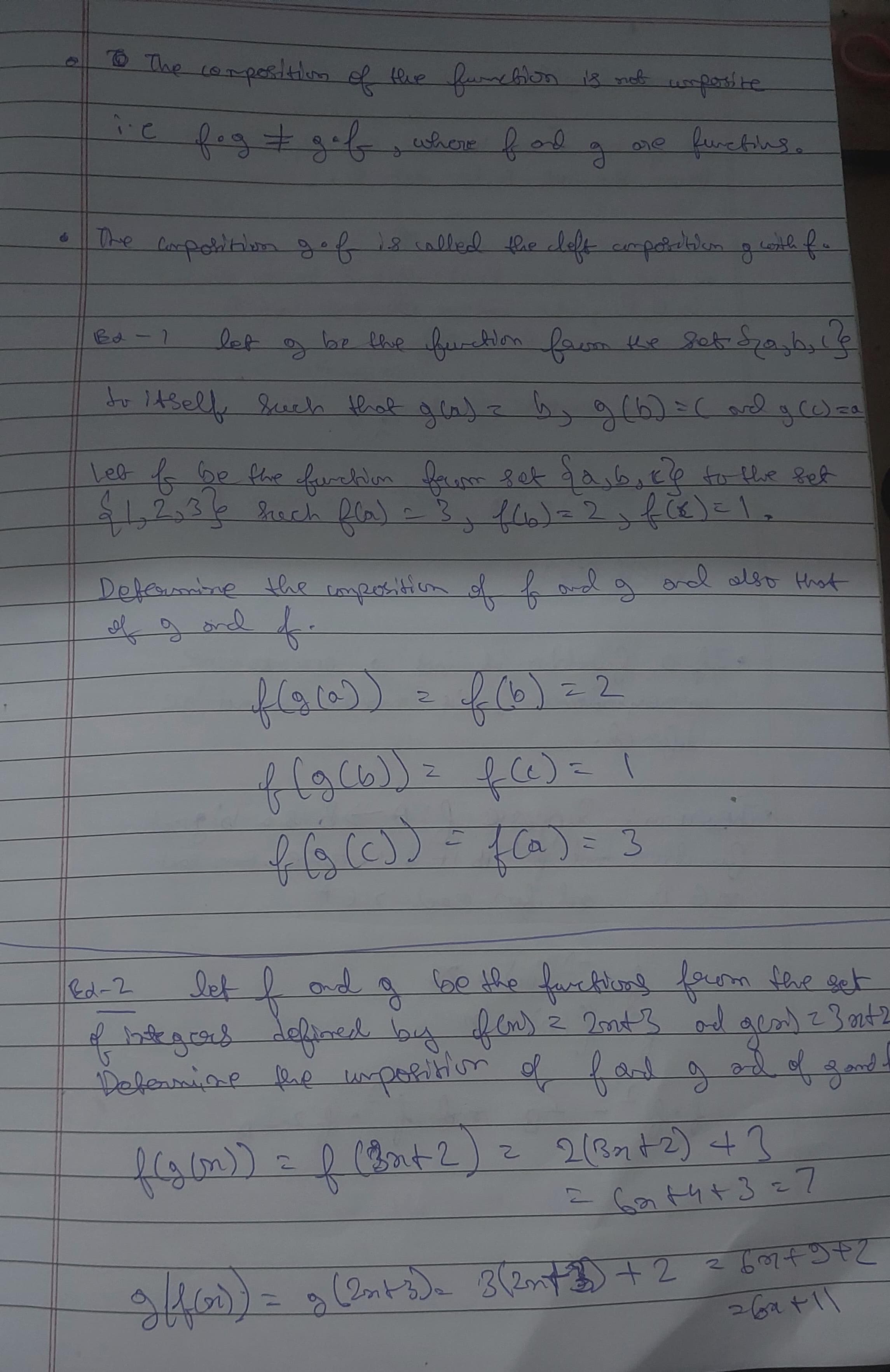

4. Composition of Functions (or Composite Functions)

A Composite function is basically a function within another function.

For example :

Let there be a function f and another function g.

The composition of f and g is given by :

The composition of the function f.g is not composite, i.e

where f and g are functions.

The composition g.f is called the left composition g with f.

Some examples on composition of functions :

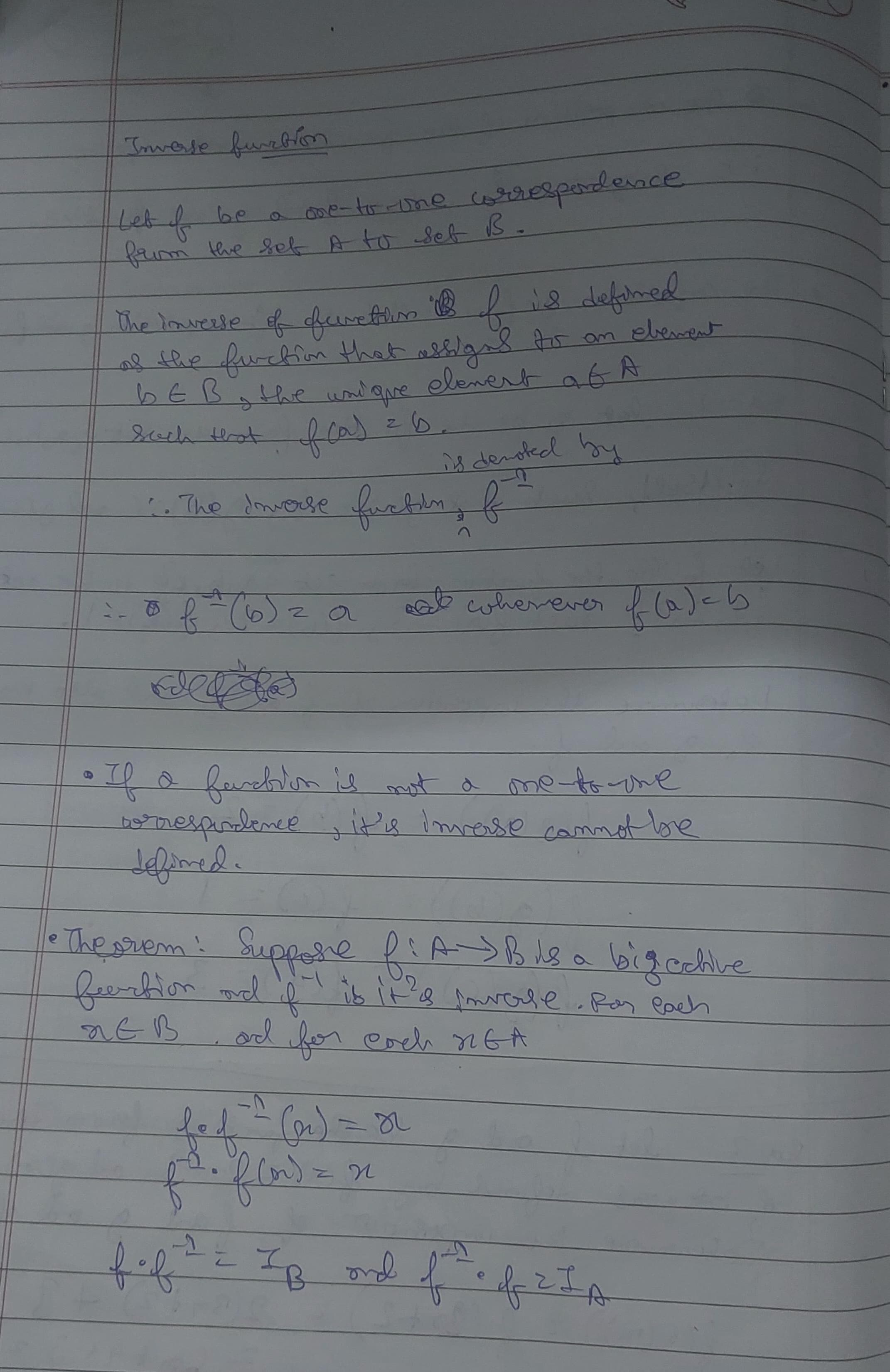

5. Inverse of a function

Let there be a one-to-one correspondence from set A to set B

Let there be a function f which assigns to an element :

,

the unique element such that :

The inverse function :

is given as

whenever,

This means that the domain and co-domains swap when the function is inversed.

However if the function is not a one-to-one correspondence then the inverse cannot be defined.

Here ,

and

are the identity functions. (Info on this not needed.)

Cantor’s Diagonal Argument.

Cantor’s diagonal argument is a mathematical proof developed by Georg Cantor that demonstrates the uncountability of the set of real numbers. This means that the set of real numbers cannot be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers, showing that there are different sizes of infinity.

Here’s a step-by-step explanation of Cantor’s diagonal argument:

-

Assumption of a Countable Set: Start by assuming that the set of real numbers (specifically, those between 0 and 1) can be listed in a sequence. This implies that we can enumerate them as follows:

Each represents a real number between 0 and 1, and can be written in it’s decimal expansion :

-

Constructing a New Number: To show that not all real numbers between 0 and 1 are in this list, Cantor constructs a new number by changing the diagonal elements of this list. Specifically, he creates a new number y such that its decimal expansion differs from the i-th number at the i-th digit. For instance, if a_ii is the i-th digit of (x_i , then the i-th digit ( b_i of y is chosen to be different from a_ii. A common way to do this is to set:

-

Ensuring the New Number is Not in the List: The number y constructed this way differs from every \x_i in at least one decimal place (the i-th decimal place). This ensures that y cannot be the same as any number in the assumed list.

-

Conclusion of Uncountability: Since y is a real number between 0 and 1 that is not in the original list, this contradicts the assumption that we had listed all real numbers between 0 and 1. Therefore, the set of real numbers between 0 and 1 cannot be countable.

Cantor’s diagonal argument shows that the set of real numbers is uncountably infinite, meaning that its cardinality (size of the set) is strictly greater than that of the set of natural numbers. This was a groundbreaking result in the history of mathematics, demonstrating that infinities can have different sizes.