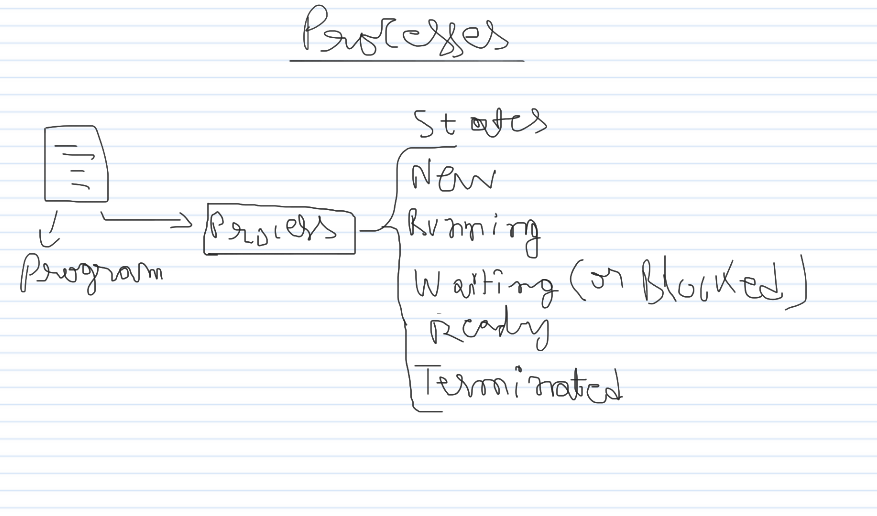

1. Processes

Definition

- A process is an instance of a program in execution. It includes the program code and its current activity.

- A process can be in one of several states during its lifetime.

Process States

Processes in an operating system can exist in several states during their execution. These states are essential for managing process scheduling and ensuring that resources are utilized efficiently. The primary process states are:

- New: The process is being created.

- Running: Instructions are being executed by the CPU.

- Waiting (or Blocked): The process is waiting for some event to occur (such as I/O completion or signal reception).

- Ready: The process is ready to be assigned to a processor.

- Terminated: The process has finished execution.

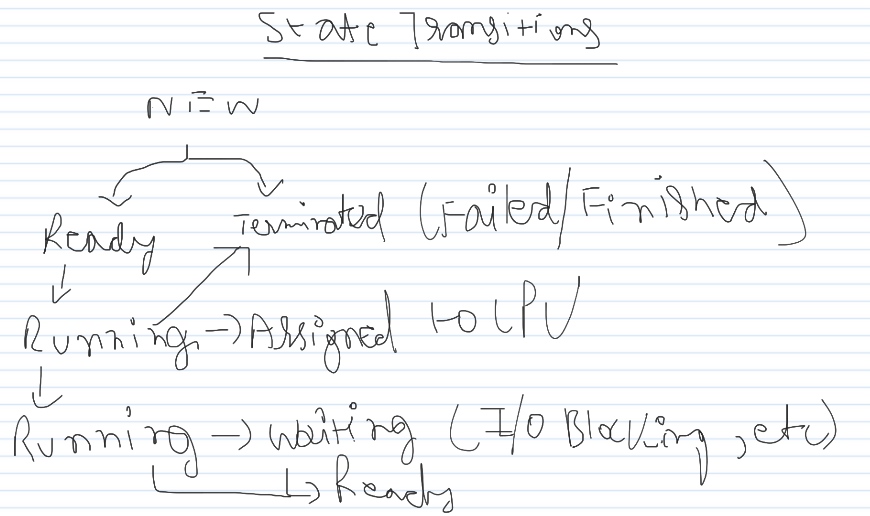

State Transitions

Processes transition between these states based on various events, such as system calls, hardware interrupts, or the completion of operations. The transitions can be visualized in a state diagram:

- New → Ready: The process has been created and is ready to run, but is not currently running.

- Ready → Running: The process is assigned to the CPU and starts execution.

- Running → Waiting: The process requires an event (like I/O) to proceed and thus enters the waiting state.

- Waiting → Ready: The event that the process was waiting for has occurred, and the process is ready to run again.

- Running → Ready: The process is preempted by the scheduler, perhaps due to the time slice being over or a higher-priority process requiring CPU time.

- Running → Terminated: The process has completed its execution and is terminated.

- New → Terminated: The process creation fails (e.g., due to insufficient memory or other resources).

Detailed Explanation of Each State Transition

1. New → Ready

When a process is created, it starts in the “new” state. This happens when a user starts an application or a system call initiates a process. The operating system allocates memory and initializes the process control block (PCB) with necessary information. Once the setup is complete, the process moves to the “ready” state, indicating that it is prepared to execute as soon as the CPU is available.

2. Ready → Running

The transition from “ready” to “running” occurs when the scheduler selects a process from the ready queue to use the CPU. This selection is based on the scheduling algorithm employed by the operating system. Once chosen, the process’s state changes to “running,” and it starts executing instructions.

3. Running → Waiting

While executing, a process may encounter situations where it cannot proceed without external events. For example, if it requires input/output (I/O) operations, it must wait for these to complete. During this waiting period, the process state changes from “running” to “waiting.” The CPU is then free to execute other processes, improving overall system efficiency.

4. Waiting → Ready

After the required event occurs (such as I/O completion or a signal reception), the waiting process becomes eligible for execution again. The operating system moves the process from the “waiting” state back to the “ready” state, where it awaits CPU allocation.

5. Running → Ready

A process in the “running” state can be preempted by the operating system if:

- Its time slice (allocated CPU time) expires.

- A higher-priority process becomes ready to run. When preempted, the process state changes from “running” to “ready,” and the process is placed back in the ready queue.

6. Running → Terminated

When a process completes its execution, it transitions from “running” to “terminated.” This means the process has finished its intended task, and the operating system de-allocates resources (like memory and open files) used by the process. The process control block (PCB) is then removed from the system.

7. New → Terminated

In some cases, a process might fail to move from the “new” to the “ready” state due to errors such as insufficient memory, invalid initialisation parameters, or security restrictions. If such a failure occurs, the process transitions directly to the “terminated” state, and the system releases any partially allocated resources.

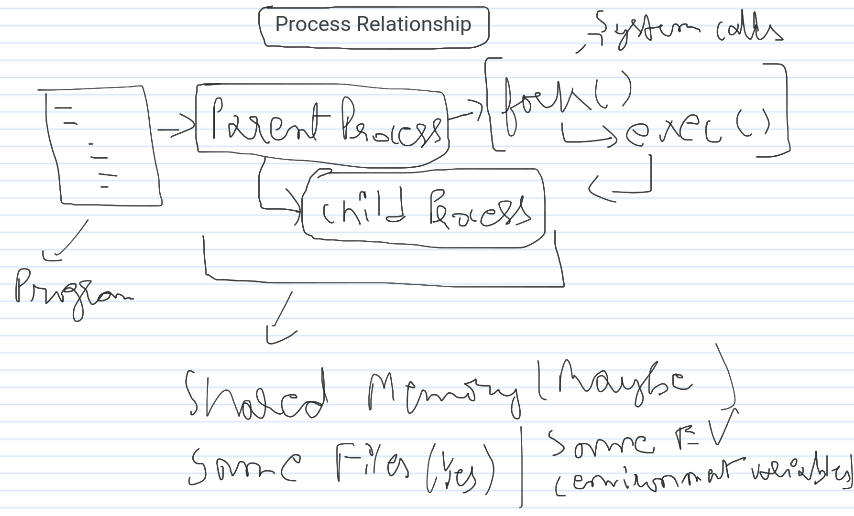

Process Relationship

Parent and Child Processes

- Parent Process: The process that creates another process.

- Child Process: The process that is created by the parent process.

When a process creates a new process, it becomes the parent of the new process, and the new process is referred to as its child. The parent and child processes can share various resources or have separate resources depending on the operating system and its implementation of process creation.

Process Creation

- Fork: In Unix-like operating systems, the

fork()system call is used to create a new process. The new process created byfork()is a copy of the parent process. - Exec: The

exec()system call replaces the current process image with a new process image, allowing a process to run a different program.

During the process creation, the following resources can be shared:

- Memory Space: The child process may have the same memory space as the parent process.

- Open Files: The child process inherits the parent’s open files.

- Environment Variables: The child process inherits the parent’s environment settings.

Process Termination

A process can terminate in several ways:

- Normal Termination: The process completes its execution and exits.

- Error Termination: The process encounters an error and exits.

- Killed by Another Process: One process can terminate another process using system calls such as

killin Unix-like operating systems. - Parent Process Termination: If a parent process terminates, its child processes may also be terminated, depending on the operating system.

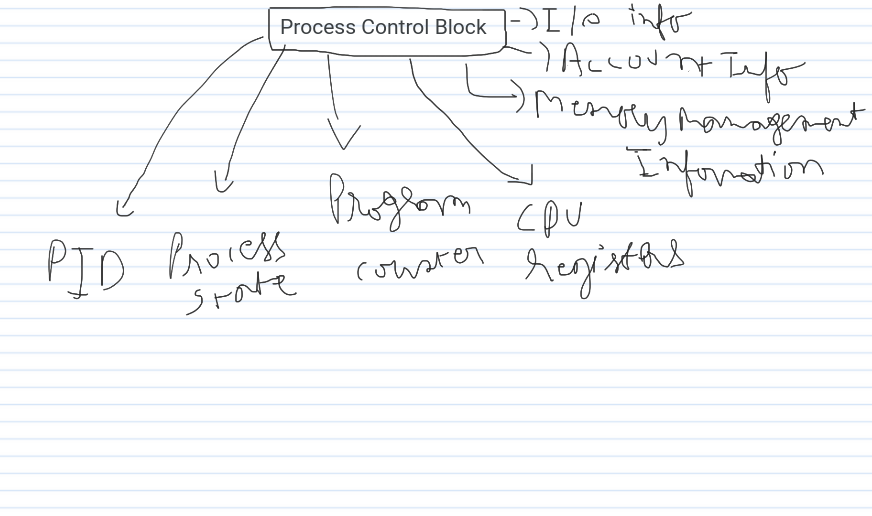

Process Control Block (PCB)

The Process Control Block (PCB) is a crucial data structure that stores information about a process. It includes:

- Process ID (PID): Unique identifier for the process.

- Process State: Current state of the process (new, ready, running, waiting, terminated).

- Program Counter: Address of the next instruction to be executed.

- CPU Registers: Contents of the CPU registers, saved when the process is preempted.

- Memory Management Information: Information about the process’s memory allocation, such as base and limit registers or page tables.

- Accounting Information: CPU usage, execution time, process limits, and other statistics.

- I/O Status Information: Information about the I/O devices allocated to the process, open files, etc.

The PCB enables the operating system to manage and control processes efficiently, ensuring that each process receives its fair share of resources and that the system operates smoothly.

Context Switching

Context switching is the process by which the operating system saves the state of a currently running process and loads the state of another process. This is essential for multitasking, allowing the CPU to switch between processes and manage multiple tasks effectively.

Steps in Context Switching

- Save the State of the Current Process: The current process’s CPU registers, program counter, and other essential information are saved in its PCB.

- Load the State of the Next Process: The next process’s PCB is loaded, and its CPU registers, program counter, and other information are restored.

- Switch to the Next Process: The CPU begins executing the instructions of the next process.

Overhead of Context Switching

Context switching incurs overhead because the CPU must save and load process states, which consumes time and resources. Reducing context switching overhead is essential for efficient multitasking and system performance.

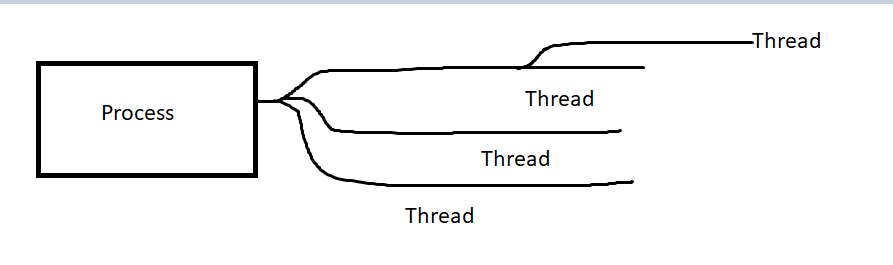

Threads: A Deep Dive into Concurrency

Definition: A thread is an independent execution path within a process. Think of it as a lightweight unit of work that can execute concurrently with other threads belonging to the same process. Each thread has its own stack, register set, and program counter, allowing them to operate independently yet share the same resources like memory space and files.

A process creating multiple threads that can work concurrently.

Various States: Threads exist in various states throughout their lifecycle:

- New: A newly created thread waiting to be started.

- Runnable: A thread that is ready to execute but hasn’t been allocated CPU time.

- Running: A thread currently being executed by the CPU.

- Blocked: A thread temporarily halted due to an event like I/O or resource waiting.

Benefits of Threads:

- Concurrency: Multiple tasks can progress seemingly simultaneously, enhancing responsiveness and overall performance.

- Resource Sharing: Threads within a process share resources efficiently, avoiding redundant memory allocation and data duplication.

- Modularity: Breaking down complex applications into smaller threads promotes modular design and easier maintenance.

- Enhanced Responsiveness: User interfaces can remain responsive even when performing lengthy background operations through separate threads.

Types of Threads:

- Kernel Threads: Managed directly by the operating system kernel, offering lightweight and efficient execution.

- User-level Threads: Created and managed by application software libraries, providing portability but relying on the kernel for scheduling.

Multithreading Concept:

Multithreading empowers a single process to execute multiple threads concurrently. This enables parallel processing and significant performance gains for tasks that can be divided into independent units of work.

Process Scheduling: Orchestrating CPU Time Allocation

Foundation & Objectives:

Process scheduling is the crucial task of deciding which process gets access to the CPU at any given time. Its primary objectives are:

- Maximize CPU Utilization: Keeping the CPU as busy as possible to achieve optimal system performance.

- Improve Throughput: Completing the maximum number of processes within a given timeframe.

- Minimize Turnaround Time: Reducing the time elapsed between a process’s submission and its completion.

- Reduce Waiting Time: Minimizing the amount of time a process spends idle while waiting for CPU access.

- Ensure Fair Resource Allocation: Providing equitable access to the CPU among competing processes.

Types of Schedulers:

- Preemptive Scheduler: Can interrupt an ongoing process and allocate the CPU to another higher-priority process, ensuring timely execution of critical tasks.

- Non-preemptive Scheduler: Once a process gains control of the CPU, it continues to execute until it voluntarily relinquishes control (e.g., completion or I/O operation).

Scheduling Criteria: Various metrics are used to evaluate scheduling algorithms:

- CPU Utilization: The percentage of time the CPU is actively engaged in processing tasks.

- Throughput: The number of processes completed per unit of time, reflecting system efficiency.

- Turnaround Time: The total time taken for a process to complete, from submission to termination.

- Waiting Time: The amount of time a process spends waiting in the ready queue for CPU access.

- Response Time: The time elapsed between a user request and the first response from the system.

Scheduling Algorithms:

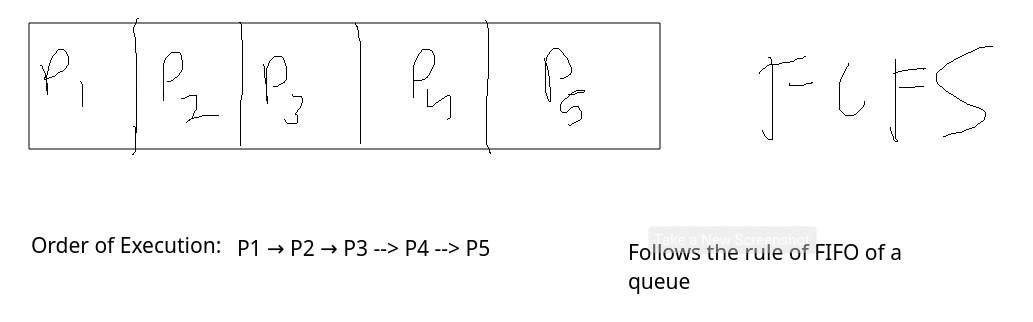

- FCFS (First Come First Served): Processes are executed in the order they arrive. Simple but prone to starvation of long-running processes.

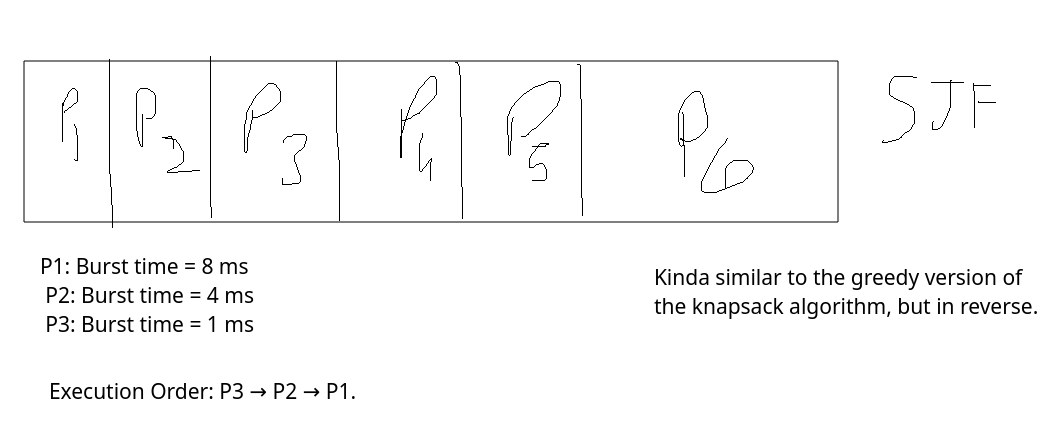

- SJF (Shortest Job First): Processes with shortest estimated execution times are prioritized, leading to reduced average waiting time.

- RR (Round Robin): Each process is allocated a fixed time slice (quantum). After the quantum expires, the CPU switches to the next ready process, ensuring fair allocation and preventing starvation.

In detail:

1. First-Come, First-Served (FCFS)

-

How It Works:

- FCFS is one of the simplest scheduling algorithms. In this algorithm, the process that arrives first in the ready queue is executed first, regardless of its burst time (the time it requires on the CPU).

- Once a process gets the CPU, it runs to completion or until it voluntarily relinquishes the CPU (i.e., non-preemptive scheduling).

-

Example:

- Consider three processes with burst times (in milliseconds) and arrival times:

- P1: Arrival time = 0 ms, Burst time = 24 ms

- P2: Arrival time = 1 ms, Burst time = 3 ms

- P3: Arrival time = 2 ms, Burst time = 3 ms

- In FCFS, P1 will run first since it arrived first, followed by P2 and then P3.

- Execution Order: P1 → P2 → P3.

- Consider three processes with burst times (in milliseconds) and arrival times:

-

Advantages:

- Simple to implement.

- No starvation (all processes eventually get executed).

-

Disadvantages:

- High average waiting time if long processes arrive first (convoy effect).

- Non-preemptive: No process can be interrupted once it starts.

Arrival Times: P1 = 0, P2 = 2, P3 = 4

Burst Times: P1 = 5, P2 = 3, P3 = 1

Execution Order: P1 -> P2 -> P3

2. Shortest Job First (SJF)

-

How It Works:

- SJF selects the process with the smallest burst time from the ready queue to execute next. There are two variations:

- Non-preemptive SJF: Once a process starts executing, it runs to completion.

- Preemptive SJF (Shortest Remaining Time First - SRTF): If a new process arrives with a shorter burst time than the remaining time of the currently running process, the current process is preempted, and the shorter process is executed.

- SJF selects the process with the smallest burst time from the ready queue to execute next. There are two variations:

-

Example:

- Consider three processes with burst times:

- P1: Burst time = 8 ms

- P2: Burst time = 4 ms

- P3: Burst time = 1 ms

- SJF (non-preemptive) will run P3 first, then P2, and finally P1.

- Execution Order: P3 → P2 → P1.

- Consider three processes with burst times:

-

Advantages:

- Minimizes the average waiting time (optimal in this sense).

- Efficient for systems where shorter tasks are more common.

-

Disadvantages:

- Requires knowledge of future burst times, which can be difficult to predict.

- Can lead to starvation if short jobs keep arriving and longer processes are never executed.

- Not suitable for interactive systems.

Arrival Times: P1 = 0, P2 = 2, P3 = 4

Burst Times: P1 = 7, P2 = 4, P3 = 1

Execution Order: P3 -> P2 -> P1

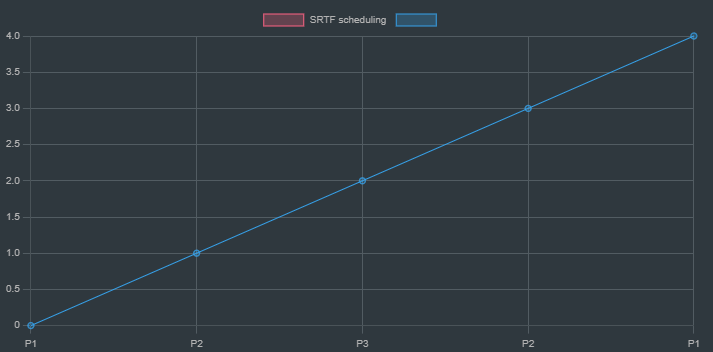

Shortest Remaining Time First (SRTF) - Preemptive SJF

How It Works:

- Preemptive version of Shortest Job First (SJF).

- The process with the shortest remaining CPU burst is always selected.

- If a new process arrives with a shorter burst time than the current process, the current process is preempted.

Example:

Let’s say we have a few processes with remaining burst times as follows:

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 8 |

| P2 | 1 | 4 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 |

Arrival Times: P1 = 0, P2 = 1, P3 = 2

Burst Times: P1 = 8, P2 = 4, P3 = 1

Execution Order: P1 -> P2 (preempts P1) -> P3(preempts P2) -> P2 -> P1- P1 starts first, but as soon as P2 arrives (burst time = 4), it preempts P1.

- P3 arrives next with a burst time of 1 and preempts P2.

- P2 then continues, followed by P1.

`A chart showing how the processes are scheduled according to SRTF`

Pros:

- Minimizes waiting time and turnaround time.

- Optimal when future CPU burst times are known or predictable.

Cons:

- Starvation: Long processes can be postponed indefinitely if shorter processes keep arriving.

- Requires accurate prediction of CPU burst times, which is difficult in real systems.

3. Round Robin (RR)

-

How It Works:

- ==In Round Robin, each process is assigned a small, fixed unit of CPU time (called the time quantum). The CPU cycles through the ready queue, giving each process a time slice to execute.==

- If a process’s burst time is longer than the time quantum, it is preempted after its time slice expires and placed back at the end of the ready queue.

- If a process completes before its time slice expires, it voluntarily gives up the CPU.

-

Example:

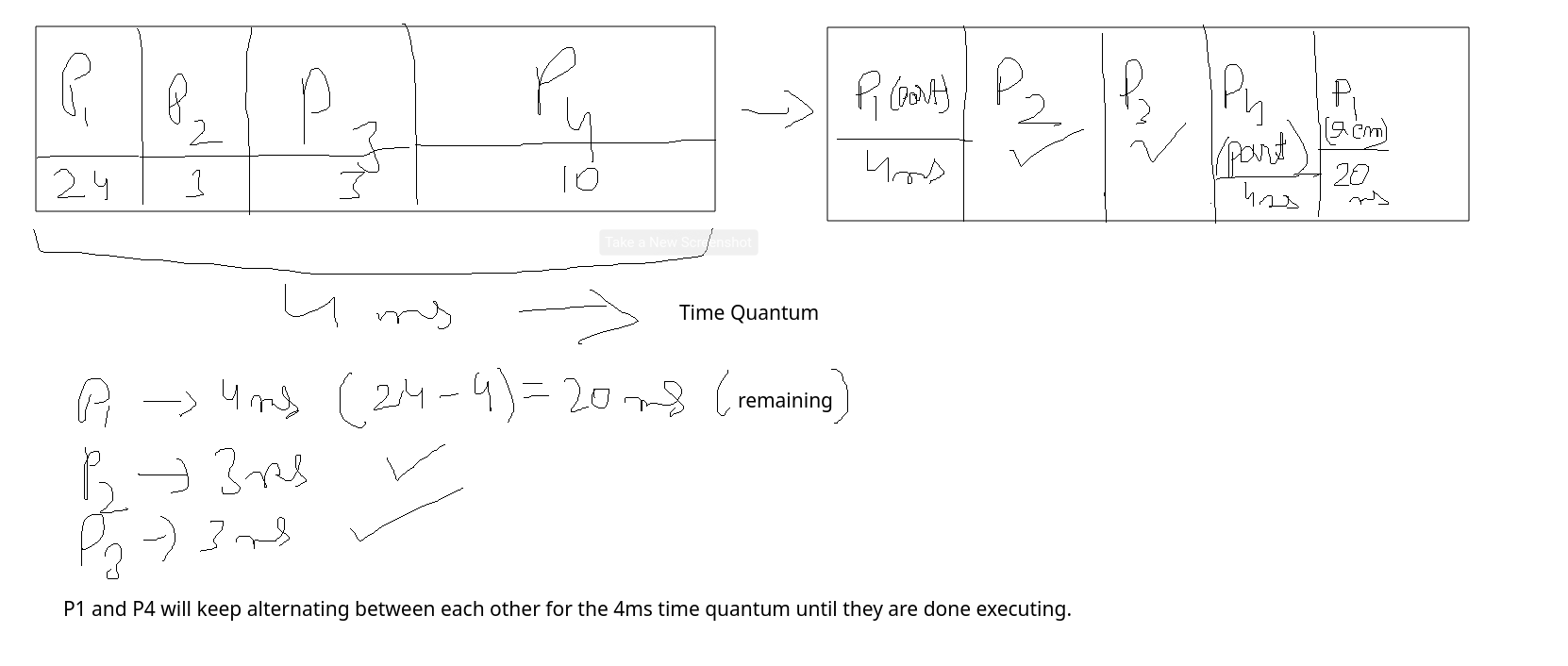

Consider these processes:

| Process | Burst Time | Time Quantum |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 24 ms | 4 ms |

| P2 | 3 ms | 4 ms |

| P3 | 3 ms | 4 ms |

| P4 | 10 ms | 4 ms |

with a given time quantum of 4ms. |

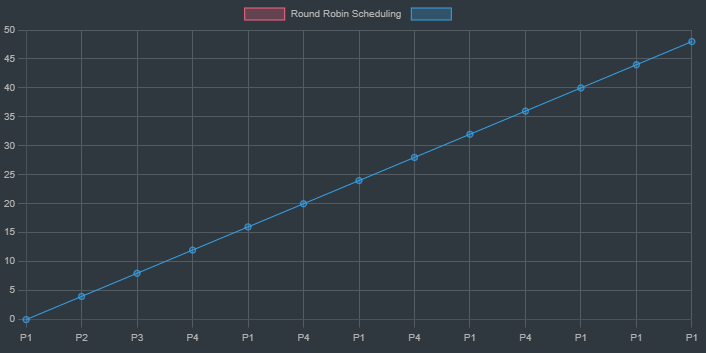

`How the processes would be scheduled and executed according to RR`

-

If the time quantum is

4 ms, the execution would proceed as follows:-

P1 executes for

4 ms, P2 executes for3 msand finishes, P3 executes for3 msand finishes. Then P1 executes for the remaining20 ms. -

Execution Order:

P1 (executes for 4ms) → P2 → P3 → P4(executes for 4ms) → P1(executes for 4ms) → P4(executes for 4ms) -> P1(executes for 4ms) -> P4(executes for 2ms) → P1(executes for 4ms) -> P1(executes for 4ms) -> P1(executes for 4ms) -> Execution complete. -

However as you can see the processes

P1andP4keep alternating back and forth in the given time quantum till the entire processes as a whole finish executing, constantly switching context back and forth.

-

-

Advantages:

- Ensures fairness: All processes get equal CPU time.

- No starvation: Every process gets to execute after a fixed interval.

-

Disadvantages:

- High context switching overhead: Frequent switching between processes can degrade performance.

- Choosing an appropriate time quantum is crucial:

- Too large: Behaves like FCFS.

- Too small: Too many context switches, wasting CPU time.

4. Priority Scheduling

-

How It Works:

- Each process is assigned a priority, and the process with the highest priority is executed first.

- Priorities can be either static (fixed) or dynamic (can change during execution).

- Two types of priority scheduling:

- Non-preemptive: The CPU is assigned to a process until it voluntarily relinquishes the CPU or finishes.

- Preemptive: If a new process with a higher priority arrives, the current process is preempted.

-

Example:

Consider three processes with their burst times and priorities as follows:

The goal here is to execute the processes in order of their ==priorities==.

| Process | Burst TImes | Priorities |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 7 | 3 |

| P2 | 4 | 1 |

| P3 | 1 | 2 |

Execution Order: P2 -> P3 -> P1-

Processes are executed based on priority (lower number = higher priority).

-

Execution Order: P2 → P3 → P1.

-

Advantages:

- Useful for systems that need to prioritize certain tasks (e.g., real-time systems).

- Flexibility to define importance through priorities.

-

Disadvantages:

- Starvation: Lower-priority processes may never get executed if high-priority processes keep arriving.

- Solution: Aging — gradually increasing the priority of a waiting process to ensure it eventually runs.

Multiprocessor Scheduling

Multiprocessor scheduling refers to the task of allocating and managing processes across multiple processors within a computer system.

The goal is to maximize system performance and resource utilization by efficiently distributing workload and minimizing idle time on any processor.

Real-Time Scheduling

Real-time scheduling is a type of scheduling algorithm used in systems where tasks have strict timing constraints.

These systems require that tasks be completed within a predetermined deadline, otherwise, the entire system’s functionality or safety could be compromised. Examples include:

- Industrial control systems

- Medical devices

- Flight control systems

Real-time scheduling algorithms prioritize tasks based on their deadlines and strive to meet all deadlines consistently.

Real-Time Scheduling Example

EDF (Earliest Deadline First) Scheduling

EDF is a real-time scheduling algorithm that prioritizes tasks based on their earliest deadlines.

The core principle of EDF is to always schedule the task with the closest deadline first, regardless of its priority level or execution time. This approach ensures that no task misses its deadline and helps maintain system responsiveness.

EDF effectively utilizes the available processing power by allocating it to tasks nearing their deadlines, minimizing the risk of a cascading effect where missed deadlines lead to further failures.

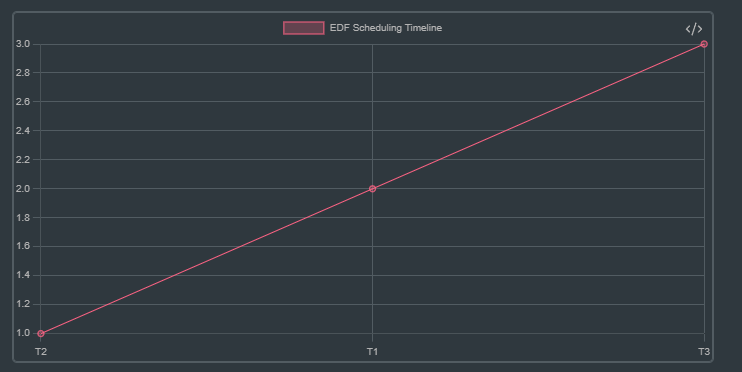

Let’s consider three processes with their respective arrival times, execution times, and deadlines:

Example:

Consider three tasks:

| Task | Execution Time | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 2ms | 6ms |

| T2 | 1ms | 4ms |

| T3 | 2ms | 8ms |

Execution Order:

- At time 0ms: All tasks are ready.

- T2 has the earliest deadline (4 ms), so it runs first.

- At time 1ms: T2 completes, T1 has the next earliest deadline (6 ms), so it runs.

- At time 3ms: T1 completes, T3 runs next since it has a deadline of 8 ms.

A real-time scheduling algorithm, such as Earliest Deadline First (EDF), would prioritize these processes based on their deadlines.

Result: All three processes are completed before their respective deadlines.

Advantages of EDF:

- Optimal Scheduling: EDF ensures that if the task set is schedulable, it will meet all deadlines. No other scheduling algorithm can guarantee meeting deadlines for a wider range of task sets.

- Flexibility: It works well in both periodic and aperiodic task systems.

- Dynamic Adjustments: Because priorities are based on deadlines, EDF can handle variations in task arrival times and execution times more gracefully.

Disadvantages of EDF:

- Overhead in Preemptive Systems: Preemptions can introduce significant overhead, especially if new tasks with earlier deadlines frequently arrive, forcing context switches.

- Unpredictable Behavior under Overload: When the system is overloaded (i.e., when deadlines cannot be met due to too many tasks), EDF may lead to a situation where many deadlines are missed. It does not prioritize which deadlines to miss first.

- Complex Implementation: Implementing EDF requires keeping track of deadlines and dynamically adjusting task priorities, which can introduce complexity and overhead, particularly in multiprocessor environments.

Rate monotonic Scheduling (RM)

Rate monotonic scheduling (RMS) is a preemptive scheduling algorithm used in real-time systems. It prioritizes tasks based on their rates, or how frequently they require execution.

The Core Principle:

Imagine you have several machines with different production cycles: one makes widgets every minute, another builds gears every 5 minutes, and a third assembles entire products every hour. If all machines need to run concurrently, RMS prioritizes the machine producing widgets because it demands attention most frequently.

In technical terms, RMS assigns priority to tasks based on the reciprocal of their periods. A task with a shorter period (executing more frequently) receives a higher priority. For example:

- Task A: Period = 10 milliseconds → Priority = 1/0.010 = 100

- Task B: Period = 50 milliseconds → Priority = 1/0.050 = 20

Order of execution: Task A ⇒ Task B

Comparison summary between RM and EDF

Comparison Summary:

| Feature | EDF | RMS |

|---|---|---|

| Priority | Dynamic (based on deadlines) | Fixed (based on periods) |

| Optimality | Optimal on uniprocessors | Optimal for static priority scheduling with periodic tasks |

| Performance under overload | Unpredictable behavior | Predictable performance but not optimal |

| Overhead | Higher due to dynamic changes | Lower due to fixed priorities |

| Suitability | Periodic and aperiodic tasks | Periodic tasks |