Index

- Intermediate Code Generation

- Intermediate Languages

- 1. Three-address code (TAC)

- 2. Abstract Syntax Trees (AST)

- 3. Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG)

- 4. Postfix evaluation.

- Three-Address Codes in Intermediate Code Generation

- Representation of TAC

- 1. Quadruples

- 2. Triples

- Problem with Triples and Execution Order

- 3. Indirect Triples

- How Indirect Triples Work

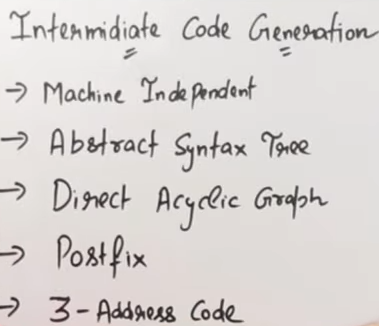

Intermediate Code Generation

Intermediate Code Generation is a crucial phase in the process of compiling a source program into machine code. It acts as a bridge between the source code and the target machine code, making the compiler design more modular and efficient. During this phase, the compiler translates the source program into an intermediate representation (IR) that is easier to analyze, manipulate, and optimize before generating the final machine code.

Purpose of Intermediate Code

- Portability: Intermediate code is platform-independent, meaning the same IR can be used for generating code for different target machines by just changing the back-end code generation.

- Optimization: Many code optimizations are easier to perform at the intermediate level than on the source or machine code.

- Simplification: It simplifies the compiler design by breaking the compilation process into multiple stages.

- Error Detection: Many semantic errors in the source code can be caught at this stage during the semantic analysis and intermediate representation generation.

Characteristics of Intermediate Representations

- Simplicity: Easier to manipulate and analyze than the source language or machine code.

- Abstraction: Provides an abstraction over the hardware, making it suitable for multiple platforms.

- Compactness: Should be compact to allow efficient storage and processing.

- Expressiveness: Must be capable of representing all constructs of the source language efficiently.

Intermediate Languages

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-bLeUysUiE&list=PLxCzCOWd7aiEKtKSIHYusizkESC42diyc&index=24

Intermediate languages are the formats or structures used to represent intermediate code. They can take several forms depending on the requirements of the compiler. Let’s explore the types of intermediate languages:

1. Three-address code (TAC):

- Represents the program as a sequence of instructions, where each instruction has at most three operands.

- Each instruction typically involves one operator and three operands: two source operands and one destination.

- Example:

t1 = a + b

t2 = t1 * c

d = t2 - e- Here,

t1,t2are temporary variables used to store intermediate results.

or

More on this is continued in Three-Address Codes in Intermediate Code Generation.

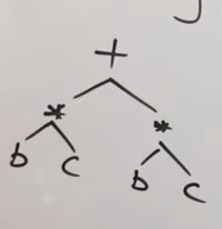

2. Abstract Syntax Trees (AST):

- A tree representation of the program’s structure based on its syntax.

- Example: For the expression

(a + b) * c, the AST would look like:

*

/ \

+ c

/ \

a b

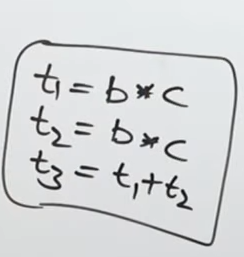

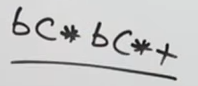

Or for the expression (b*c) + (b*c):

This would be an AST for the expression.

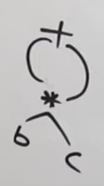

3. Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG):

- A condensed form of AST that eliminates redundant computations by sharing sub-expressions.

- Example: If

(a + b)is computed multiple times in a program, it would appear as a single node in the DAG.

Or for the expression (b*c) + (b*c):

This image would be an accurate DAG representation for the expression.

4. Postfix evaluation.

This is similar to the postfix evaluation done in DSA.

The process of postfix evaluation is detailed here: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/evaluation-of-postfix-expression/

or a video explanation here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84BsI5VJPq4

Three-Address Codes in Intermediate Code Generation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJUYVGDn0JE&list=PLxCzCOWd7aiEKtKSIHYusizkESC42diyc&index=23

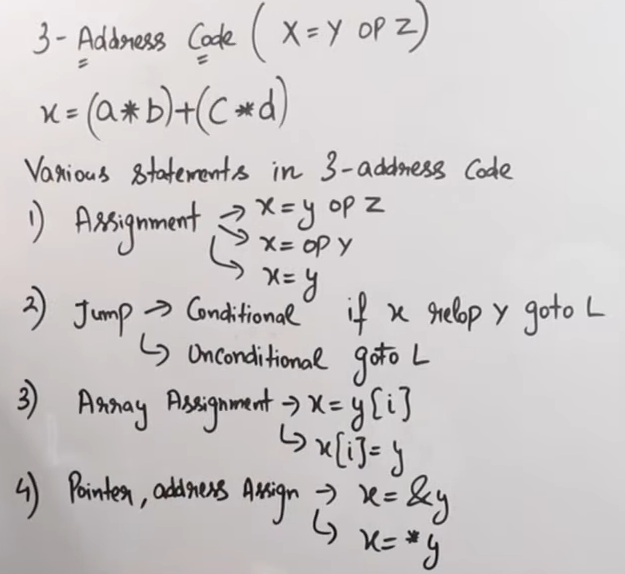

Structure of TAC

A typical three-address code instruction is of the form:

x = y op zWhere:

x: The destination or result variable.y,z: Source operands (could be variables, constants, or temporary variables).op: An operator (e.g., arithmetic, logical, or relational).

Advantages of TAC

- Modularity: It breaks complex operations into simpler steps, making the program easier to analyze.

- Optimization: TAC provides a clear structure for applying optimization techniques like common subexpression elimination, constant folding, and dead code elimination.

- Simplicity: Its simplicity makes it easier to generate machine code for different architectures.

- Portability: TAC is platform-independent, allowing the same representation to be used across different backends.

Types of Three-Address Code Instructions:

Terminologies which might look confusing:

- relop : “Relational operator”

- “op”: “Operator”

- Assignment Statements:

x = y op zExample: t1 = a + b

- Unary Operations:

x = op yExample: t1 = -a (negation)

- Copy Instructions:

x = yExample: t1 = a

- Unconditional Jumps:

goto LExample: goto L1

- Conditional Jumps:

if x relop y goto LExample: if a > b goto L2

- Indexed Assignments:

x = y[i]

y[i] = xExample:

t1 = A[i] // Read from array

A[i] = t2 // Write to array- Function Calls and Returns:

param x

call P, n

x = call P, n

return xExample:

param a

call foo, 1

return t1Representation of TAC

Three-address code can be represented in three forms:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0HCUfGsEK0

1. Quadruples:

- Each instruction is represented as a tuple of four fields, each with a final result name.:

(operator, arg1, arg2, result)- Example: For

t1 = a + b

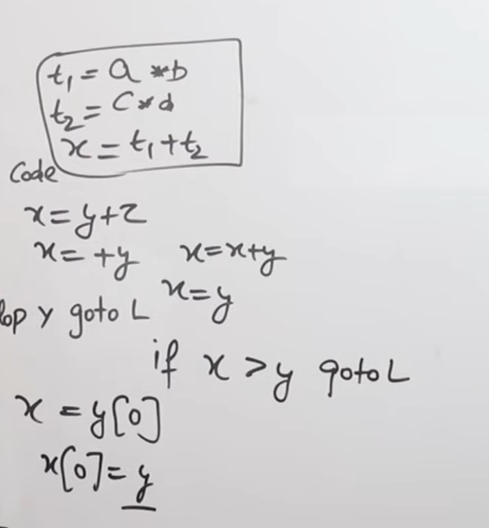

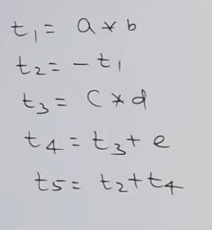

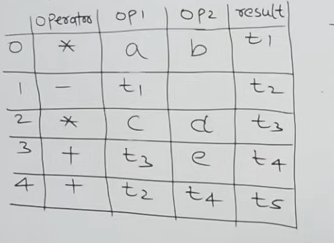

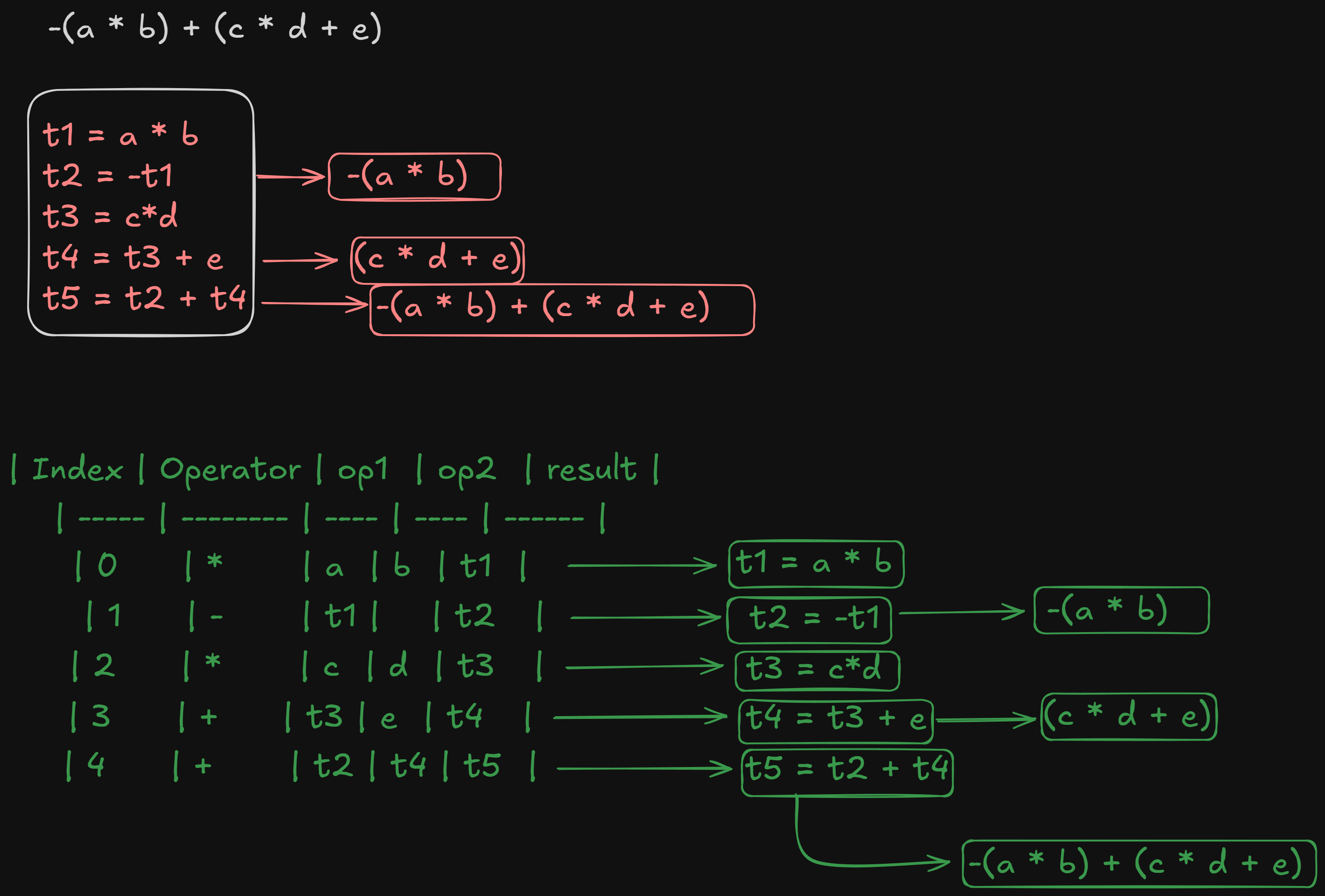

(+, a, b, t1)- Example 2: For expression

-(a * b) + (c * d + e):

This would be the generated three-address code

And this would be it’s quadruple representation :

or

| Index | Operator | op1 | op2 | result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | a | b | t1 |

| 1 | - | t1 | t2 | |

| 2 | * | c | d | t3 |

| 3 | + | t3 | e | t4 |

| 4 | + | t2 | t4 | t5 |

or an even better explanation :

2. Triples

- Each instruction is represented as a tuple of three fields, without a direct result name.

(operator, arg1, arg2)- Example: For

t1 = a + bfollowed byt2 = t1 * c

(1) (+, a, b)

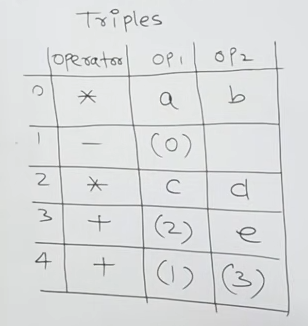

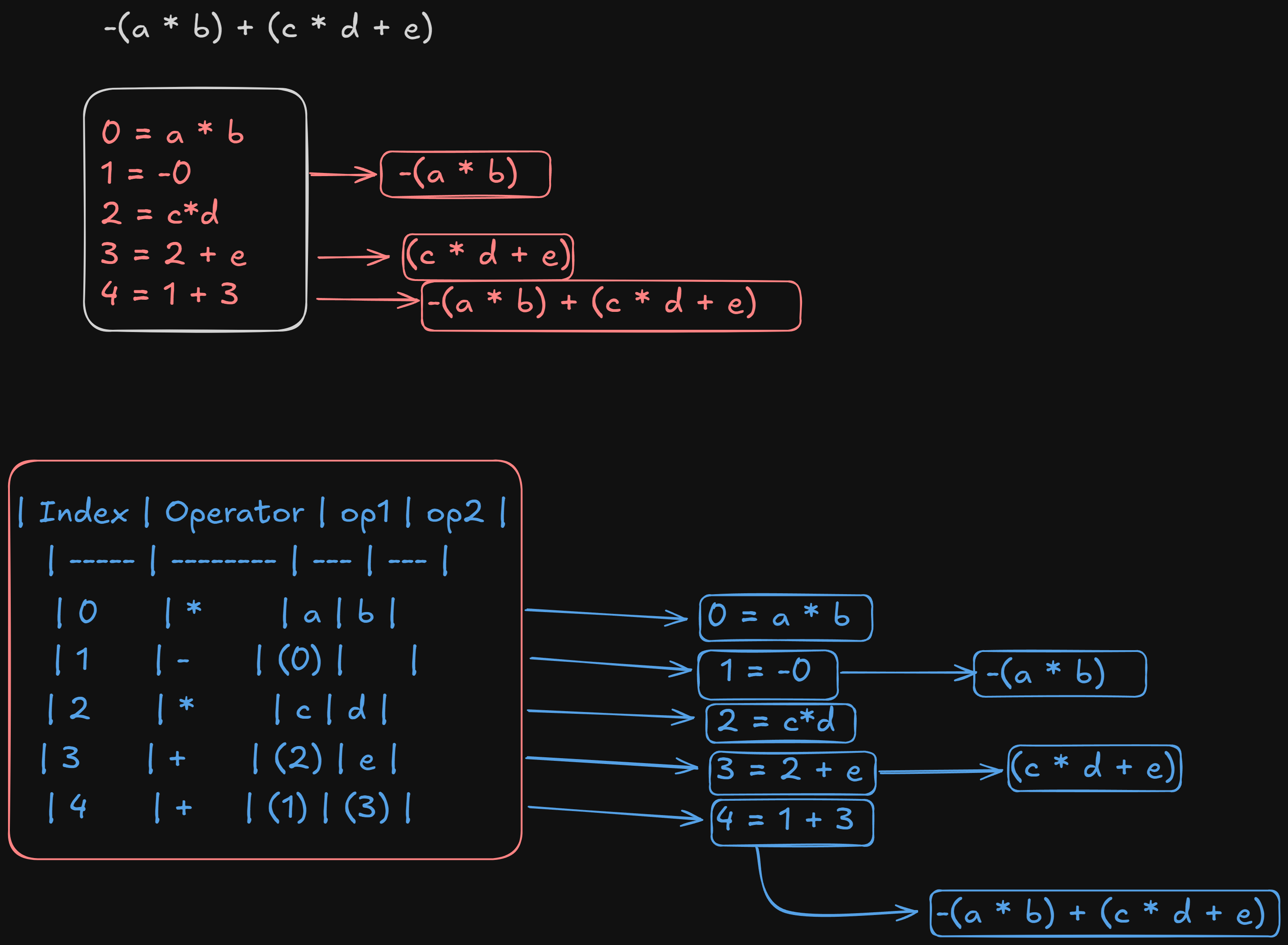

(2) (*, (1), c)- Example 2: For expression

-(a * b) + (c * d + e):

or

| Index | Operator | op1 | op2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | a | b |

| 1 | - | (0) | |

| 2 | * | c | d |

| 3 | + | (2) | e |

| 4 | + | (1) | (3) |

The values like (0), (1), (2) and (3) are pointers which point to that specific instruction’s memory location.

Explanation:

- Index 0:

a * bis computed, and its result is stored at(0). - Index 1: The negation operator (

-) is applied to the result at(0). This means that instruction 1 retrieves the result produced by instruction 0 and applies the negation. - Index 2:

c * dis computed, and its result is stored at(2). - Index 3: The addition

c * d + eis computed using the result at(2)and the operande. - Index 4: Finally, the addition of

-(a * b)(result at(1)) and(c * d + e)(result at(3)) is computed.

Pointers in Triples:

- Indexes like

(0)or(2)refer to the results of the respective instructions. These are implicit pointers, meaning the actual data resides in temporary memory locations, and the triple simply points to them. - When generating the machine or assembly code later, these pointers will be translated into actual memory locations, registers, or stack offsets.

Problem with Triples and Execution Order

For example if we were to execute instruction (2) first, it will be assigned as instruction (0) now, and it’s value in instruction (1) which is supposed to be -(0) (expected -a*b), now becomes (-c*d) instead.

In the triples representation:

- Operands such as

(0)or(2)refer to the index of the instruction in the triples table. - The order of execution must strictly follow the sequence given in the table. If the order changes during code generation or optimization, the meaning of the references could change, leading to incorrect results.

Example: Reordering in the Table

Original Table:

| Index | Operator | op1 | op2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | a | b |

| 1 | - | (0) | |

| 2 | * | c | d |

| 3 | + | (2) | e |

| 4 | + | (1) | (3) |

Here:

- Instruction

(0)computesa * b. - Instruction

(1)uses(0)to compute-(a * b).

If Instructions are Executed Out of Order (e.g., (2) before (0)):

| Index | Operator | op1 | op2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | c | d |

| 1 | - | (0) | |

| 2 | * | a | b |

Here’s what happens:

- The result of

(1)is now-(c * d)instead of-(a * b), which is wrong. - The dependency on instruction indexes makes triples highly sensitive to execution order.

Why This Happens

- In triples, references like

(0)are positional, not semantic. They assume the instructions will be executed in the exact order listed in the table. - Reordering instructions during optimization or due to parallelism can break this assumption.

Solutions to Avoid This Issue

1. Stick to Fixed Order During Execution

- The simplest solution is to execute instructions in the order they appear in the triples table. However, this limits optimization opportunities (e.g., moving independent instructions for better performance).

2. Use Quadruples Instead

- In quadruples, instead of relying on positional references like

(0), we use explicit temporary variables (e.g.,t1,t2). For example:

t1 = a * b

t2 = -t1

t3 = c * d

t4 = t3 + e

t5 = t2 + t4- Since each intermediate result has a unique name (

t1,t2, etc.), execution order does not affect correctness.

3. Static Single Assignment (SSA) Form

- Another alternative is to use SSA form, where each intermediate variable is assigned only once. This makes dependencies clear and prevents ambiguity.

4. Include Dependencies in Triple Representation

- Instead of relying on indexes, triples could explicitly track dependencies between instructions (e.g., a dependency graph). However, this complicates implementation.

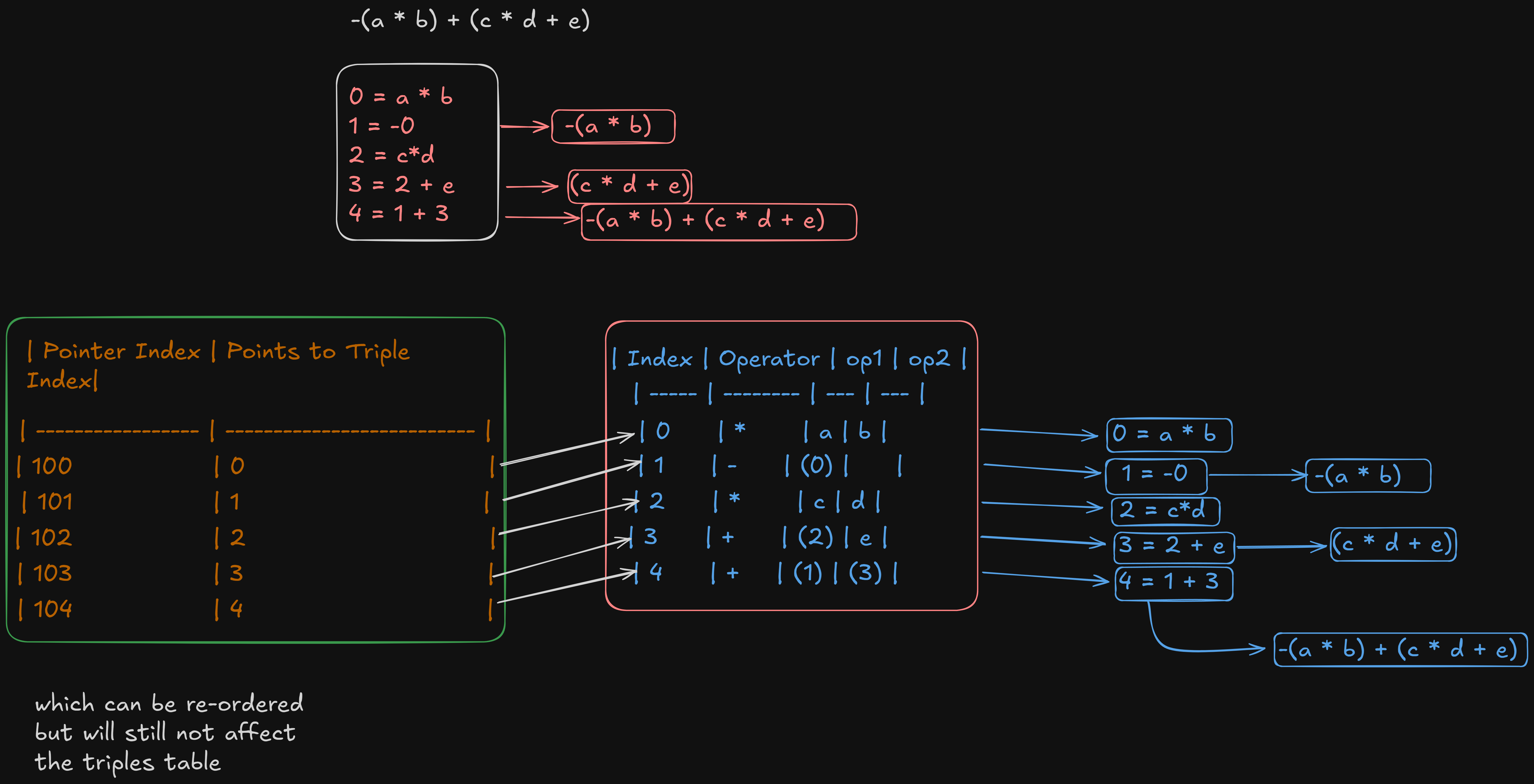

3. Indirect Triples

Indirect triples are a variation of the triples representation, introduced to address some of the limitations of direct triples, especially the order-dependency issue that I raised earlier.

How Indirect Triples Work

- Instead of referencing instructions using positional indices, an additional table (called a pointer table or index table) is used to store pointers to the actual triples.

- Each entry in the pointer table points to a specific triple in the triples table.

- By using this intermediate layer of indirection, reordering of instructions becomes feasible without breaking references.

Structure of Indirect Triples

-

Pointer Table:

- This table contains entries that point to the triples table.

- Each pointer can be reordered without changing the underlying triples.

-

Triples Table:

- Contains the actual instructions in the for

Example

Let’s use the same expression as before:

-(a * b) + (c * d + e)

Step 1: Triples Table

| Index | Operator | op1 | op2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | a | b |

| 1 | - | (0) | |

| 2 | * | c | d |

| 3 | + | (2) | e |

| 4 | + | (1) | (3) |

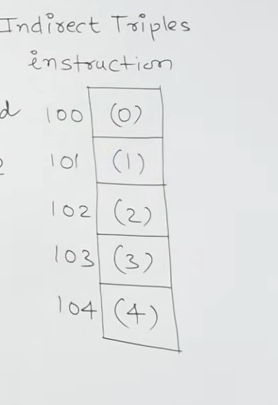

Step 2: Pointer Table

| Pointer Index | Points to Triple Index |

|---|---|

| 100 | 0 |

| 101 | 1 |

| 102 | 2 |

| 103 | 3 |

| 104 | 4 |

These pointers store the locations to the pointer instructions within the triples table.

The drawback for this type of representation is that it uses twice the memory for the representation since there are two sets of pointers being used per instruction.

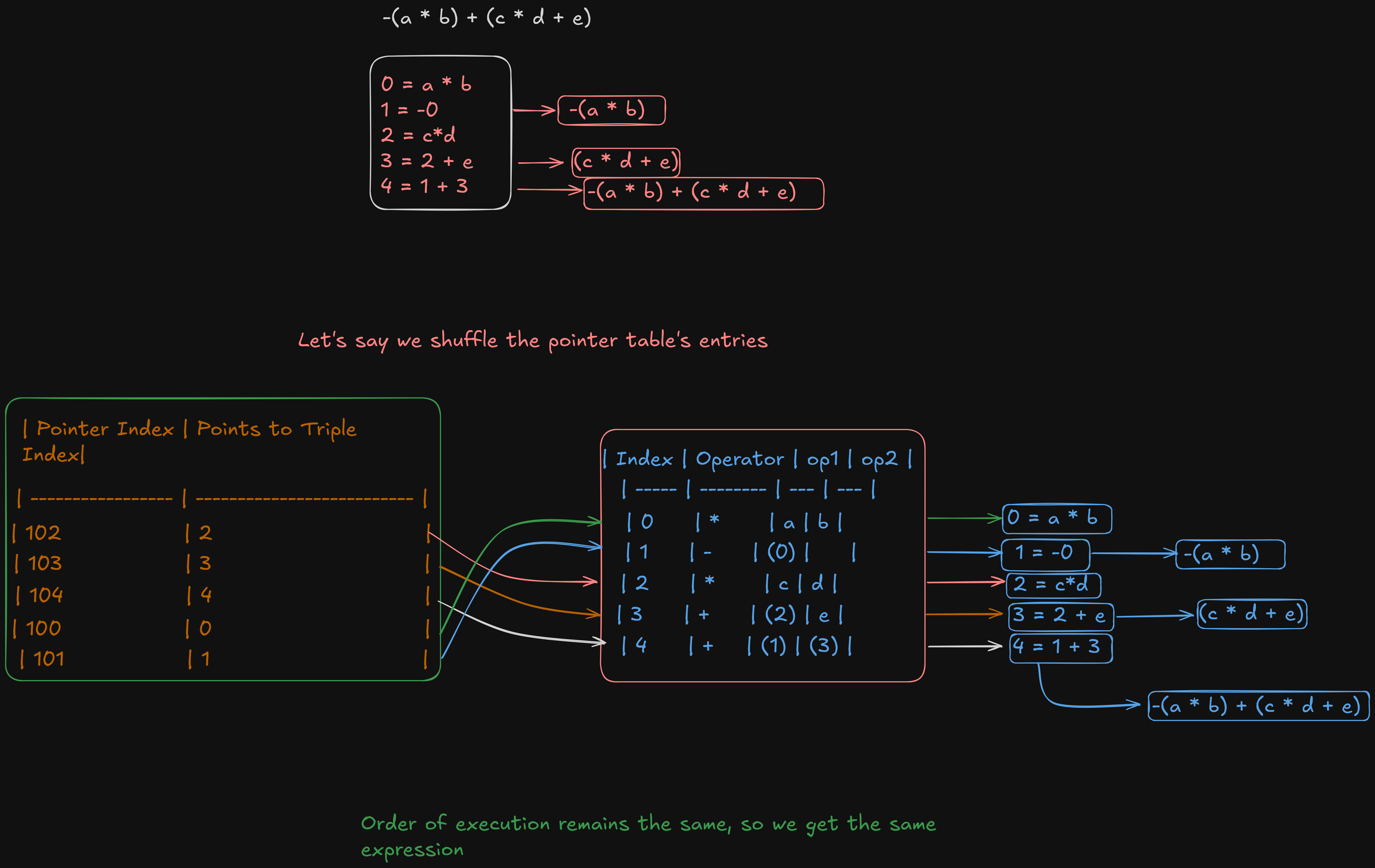

Now, let’s say we shuffle the order of execution in the pointer table. Will we still get the original expression?

So yeah, we still get the same expression.